go full text search

让我们构建一个全文搜索引擎

全文搜索是人们每天都在使用却没有意识到的工具之一。如果你曾经在 Google 上搜索过“golang 覆盖率报告”或在电子商务网站上搜索过“室内无线摄像头”,那么你就使用了某种全文搜索。

全文搜索 (FTS) 是一种在文档集合中搜索文本的技术。文档可以指网页、报纸文章、电子邮件或任何结构化文本。

今天我们要构建自己的 FTS 引擎。在这篇文章结束时,我们将能够在不到一毫秒的时间内搜索数百万个文档。我们将从简单的搜索查询开始,例如“给我包含单词cat的所有文档”,然后我们将扩展引擎以支持更复杂的布尔查询。

笔记

最著名的 FTS 引擎是Lucene(以及建立在其之上的Elasticsearch和 Solr)。

为什么选择FTS

在开始编写代码之前,您可能会问“我们不能只使用grep或循环检查每个文档是否包含我要查找的单词吗?”。是的,我们可以。但是,这并不总是最好的主意。

语料库

我们将搜索英文维基百科摘要的一部分。最新的转储可在dumps.wikimedia.org上找到。截至今天,解压后的文件大小为 913 MB。XML 文件包含超过 600K 个文档。

文档示例:

<title>Wikipedia: Kit-Cat Klock</title>

<url>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kit-Cat_Klock</url>

<abstract>The Kit-Cat Klock is an art deco novelty wall clock shaped like a grinning cat with cartoon eyes that swivel in time with its pendulum tail.</abstract>

加载文档

首先,我们需要从转储中加载所有文档。内置的encoding/xml包非常方便:

import (

"encoding/xml"

"os"

)

type document struct {

Title string `xml:"title"`

URL string `xml:"url"`

Text string `xml:"abstract"`

ID int

}

func loadDocuments(path string) ([]document, error) {

f, err := os.Open(path)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

defer f.Close()

dec := xml.NewDecoder(f)

dump := struct {

Documents []document `xml:"doc"`

}{}

if err := dec.Decode(&dump); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

docs := dump.Documents

for i := range docs {

docs[i].ID = i

}

return docs, nil

}

每个加载的文档都会被分配一个唯一的标识符。为简单起见,第一个加载的文档被分配 ID=0,第二个被分配 ID=1,依此类推。

首次尝试

搜索内容

现在我们已将所有文档加载到内存中,我们可以尝试查找有关猫的文档。首先,让我们循环遍历所有文档并检查它们是否包含子字符串cat:

func search(docs []document, term string) []document {

var r []document

for _, doc := range docs {

if strings.Contains(doc.Text, term) {

r = append(r, doc)

}

}

return r

}

在我的笔记本电脑上,搜索阶段耗时 103 毫秒 - 还不错。如果您从输出中抽查一些文档,您可能会注意到该函数匹配caterpillar和category,但没有匹配大写C 的__Cat。这不是我想要的。

在继续前进之前,我们需要解决两个问题:

- 使搜索不区分大小写(因此Cat也匹配)。

- 在单词边界上匹配而不是在子字符串上匹配(因此caterpillar和communication不匹配)。

使用正则表达式搜索

我很快想到的一个可以实现这两个要求的解决方案就是正则表达式。

这里是 - (?i)\bcat\b:

- (?i)使正则表达式不区分大小写

- \b匹配单词边界(一侧是单词字符而另一侧不是单词字符的位置)

func search(docs []document, term string) []document {

re := regexp.MustCompile(`(?i)\b` + term + `\b`) // Don't do this in production, it's a security risk. term needs to be sanitized.

var r []document

for _, doc := range docs {

if re.MatchString(doc.Text) {

r = append(r, doc)

}

}

return r

}

搜索花了 2 秒多的时间。如您所见,即使有 600K 份文档,速度也开始变慢。虽然这种方法很容易实现,但扩展性不好。随着数据集越来越大,我们需要扫描越来越多的文档。该算法的时间复杂度是线性的 - 需要扫描的文档数量等于文档总数。如果我们有 6M 份文档而不是 600K 份,搜索将花费 20 秒。我们需要做得更好。

倒排索引#

为了加快搜索查询速度,我们将对文本进行预处理并提前建立索引。

FTS 的核心是一种叫做倒排索引的数据结构。倒排索引将文档中的每个单词与包含该单词的文档关联起来。

例子:

documents = {

1: "a donut on a glass plate",

2: "only the donut",

3: "listen to the drum machine",

}

index = {

"a": [1],

"donut": [1, 2],

"on": [1],

"glass": [1],

"plate": [1],

"only": [2],

"the": [2, 3],

"listen": [3],

"to": [3],

"drum": [3],

"machine": [3],

}

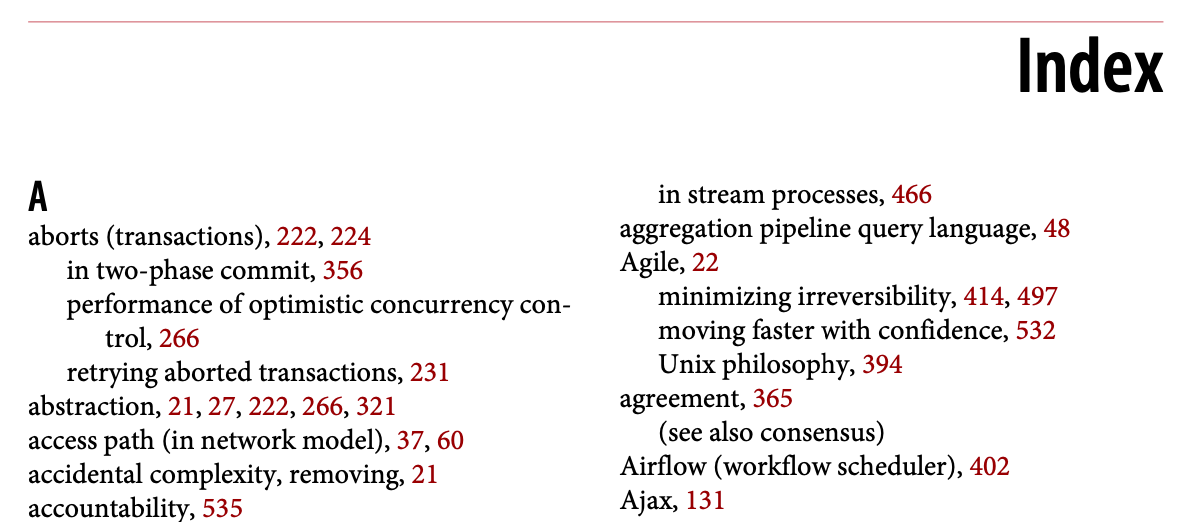

以下是倒排索引的真实示例。书中的索引中,术语引用页码:

文本分析

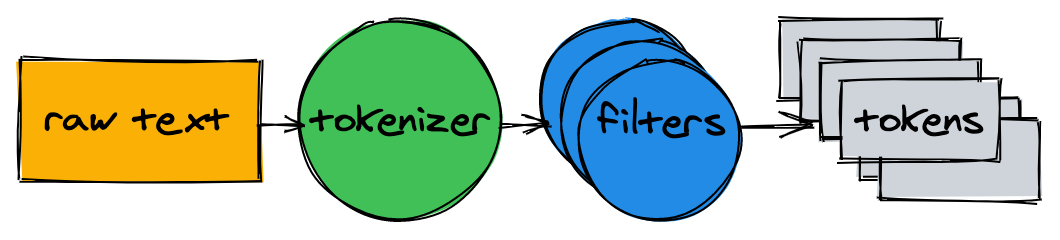

在开始构建索引之前,我们需要将原始文本分解为适合索引和搜索的单词列表(标记)。

文本分析器由一个标记器和多个过滤器组成。

标记器

标记器是文本分析的第一步。它的作用是将文本转换为标记列表。我们的实现在单词边界上拆分文本并删除标点符号:

func tokenize(text string) []string {

return strings.FieldsFunc(text, func(r rune) bool {

// Split on any character that is not a letter or a number.

return !unicode.IsLetter(r) && !unicode.IsNumber(r)

})

}

> tokenize("A donut on a glass plate. Only the donuts.")

["A", "donut", "on", "a", "glass", "plate", "Only", "the", "donuts"]

过滤器#

在大多数情况下,仅将文本转换为标记列表是不够的。为了使文本更易于索引和搜索,我们需要进行额外的规范化。

小写#

为了使搜索不区分大小写,小写过滤器将标记转换为小写。cAt、Cat和_caT被规范化为_cat。稍后,当我们查询索引时,我们也会将搜索词转换为小写。这将使搜索词cAt与文本Cat匹配。

func lowercaseFilter(tokens []string) []string {

r := make([]string, len(tokens))

for i, token := range tokens {

r[i] = strings.ToLower(token)

}

return r

}

> lowercaseFilter([]string{"A", "donut", "on", "a", "glass", "plate", "Only", "the", "donuts"})

["a", "donut", "on", "a", "glass", "plate", "only", "the", "donuts"]

删除常用词

几乎所有的英文文本都包含常用的单词,例如a、I、the_或_be。这些词被称为停用词。我们将删除它们,因为几乎所有文档都会匹配停用词。

没有“官方”的停用词列表。让我们根据OEC 排名排除前 10 个。请随意添加更多:

var stopwords = map[string]struct{}{ // I wish Go had built-in sets.

"a": {}, "and": {}, "be": {}, "have": {}, "i": {},

"in": {}, "of": {}, "that": {}, "the": {}, "to": {},

}

func stopwordFilter(tokens []string) []string {

r := make([]string, 0, len(tokens))

for _, token := range tokens {

if _, ok := stopwords[token]; !ok {

r = append(r, token)

}

}

return r

}

> stopwordFilter([]string{"a", "donut", "on", "a", "glass", "plate", "only", "the", "donuts"})

["donut", "on", "glass", "plate", "only", "donuts"]

Stemming #

Because of the grammar rules, documents may include different forms of the same word. Stemming reduces words into their base form. For example, fishing, fished and fisher may be reduced to the base form (stem) fish.

Implementing a stemmer is a non-trivial task, it's not covered in this post. We'll take one of the existing modules:

import snowballeng "github.com/kljensen/snowball/english"

func stemmerFilter(tokens []string) []string {

r := make([]string, len(tokens))

for i, token := range tokens {

r[i] = snowballeng.Stem(token, false)

}

return r

}

> stemmerFilter([]string{"donut", "on", "glass", "plate", "only", "donuts"})

["donut", "on", "glass", "plate", "only", "donut"]

Note

A stem is not always a valid word. For example, some stemmers may reduce airline to airlin.

Putting the analyzer together #

func analyze(text string) []string {

tokens := tokenize(text)

tokens = lowercaseFilter(tokens)

tokens = stopwordFilter(tokens)

tokens = stemmerFilter(tokens)

return tokens

}

The tokenizer and filters convert sentences into a list of tokens:

> analyze("A donut on a glass plate. Only the donuts.")

["donut", "on", "glass", "plate", "only", "donut"]

The tokens are ready for indexing.

Building the index #

Back to the inverted index. It maps every word in documents to document IDs. The built-in map is a good candidate for storing the mapping. The key in the map is a token (string) and the value is a list of document IDs:

type index map[string][]int

Building the index consists of analyzing the documents and adding their IDs to the map:

func (idx index) add(docs []document) {

for _, doc := range docs {

for _, token := range analyze(doc.Text) {

ids := idx[token]

if ids != nil && ids[len(ids)-1] == doc.ID {

// Don't add same ID twice.

continue

}

idx[token] = append(ids, doc.ID)

}

}

}

func main() {

idx := make(index)

idx.add([]document{{ID: 1, Text: "A donut on a glass plate. Only the donuts."}})

idx.add([]document{{ID: 2, Text: "donut is a donut"}})

fmt.Println(idx)

}

It works! Each token in the map refers to IDs of the documents that contain the token:

map[donut:[1 2] glass:[1] is:[2] on:[1] only:[1] plate:[1]]

Querying #

To query the index, we are going to apply the same tokenizer and filters we used for indexing:

func (idx index) search(text string) [][]int {

var r [][]int

for _, token := range analyze(text) {

if ids, ok := idx[token]; ok {

r = append(r, ids)

}

}

return r

}

> idx.search("Small wild cat")

[[24, 173, 303, ...], [98, 173, 765, ...], [[24, 51, 173, ...]]

And finally, we can find all documents that mention cats. Searching 600K documents took less than a millisecond (18µs)!

With the inverted index, the time complexity of the search query is linear to the number of search tokens. In the example query above, other than analyzing the input text, search had to perform only three map lookups.

Boolean queries #

The query from the previous section returned a disjoined list of documents for each token. What we normally expect to find when we type small wild cat in a search box is a list of results that contain small, wild and cat at the same time. The next step is to compute the set intersection between the lists. This way we'll get a list of documents matching all tokens.

!https://artem.krylysov.com/images/2020-fts/venn.png

Luckily, IDs in our inverted index are inserted in ascending order. Since the IDs are sorted, it's possible to compute the intersection between two lists in linear time. The intersection function iterates two lists simultaneously and collects IDs that exist in both:

func intersection(a []int, b []int) []int {

maxLen := len(a)

if len(b) > maxLen {

maxLen = len(b)

}

r := make([]int, 0, maxLen)

var i, j int

for i < len(a) && j < len(b) {

if a[i] < b[j] {

i++

} else if a[i] > b[j] {

j++

} else {

r = append(r, a[i])

i++

j++

}

}

return r

}

Updated search analyzes the given query text, lookups tokens and computes the set intersection between lists of IDs:

func (idx index) search(text string) []int {

var r []int

for _, token := range analyze(text) {

if ids, ok := idx[token]; ok {

if r == nil {

r = ids

} else {

r = intersection(r, ids)

}

} else {

// Token doesn't exist.

return nil

}

}

return r

}

The Wikipedia dump contains only two documents that match small, wild and cat at the same time:

> idx.search("Small wild cat")

130764 The wildcat is a species complex comprising two small wild cat species, the European wildcat (Felis silvestris) and the African wildcat (F. lybica).

131692 Catopuma is a genus containing two Asian small wild cat species, the Asian golden cat (C. temminckii) and the bay cat.

The search is working as expected!

顺便说一句,这是我第一次听说catopuma,其中之一如下:

!https://artem.krylysov.com/images/2020-fts/asian-golden-cat-s.jpg

结论

我们刚刚构建了一个全文搜索引擎。尽管它很简单,但它可以为更高级的项目奠定坚实的基础。

我没有涉及很多可以显著提高性能并使引擎更加用户友好的事情。以下是一些进一步改进的想法:

- 扩展布尔查询以支持OR和NOT。

- 将索引存储在磁盘上:

- 每次重新启动应用程序时重建索引可能需要一段时间。

- 大型索引可能不适合内存。

- 尝试使用内存和 CPU 高效的数据格式来存储文档 ID 集。查看Roaring Bitmaps。

- 支持索引多个文档字段。

- 按相关性对结果进行排序。

完整的源代码可以在GitHub上找到。